Thinking about this post I realised how long I hadn’t written anything about Alfred Jarry. I have been preoccupied with my new project and every since my book on Jarry was published in 2012 (yes, shameless plug) I have unfortunately neglected him a bit. I lived with Jarry for more years than I care to remember (he was the topic of my MA dissertation and my PhD thesis), but I still find myself revisiting his work every now and then. Not always for research related reasons. Whenever I am in need of some humour and creativity to counter the self-important earnestness of certain corners of academia, I turn to the infinite wisdom of Père Ubu and his almanacs. Many copies of the Almanach illustré du Père Ubu, the first one published in 1899 and the second almanac in 1901, remained unsold at the time. However, I’d like to think that Jarry would have appreciated that at least one person would be carrying them around religiously more than a century later. That one person being me.

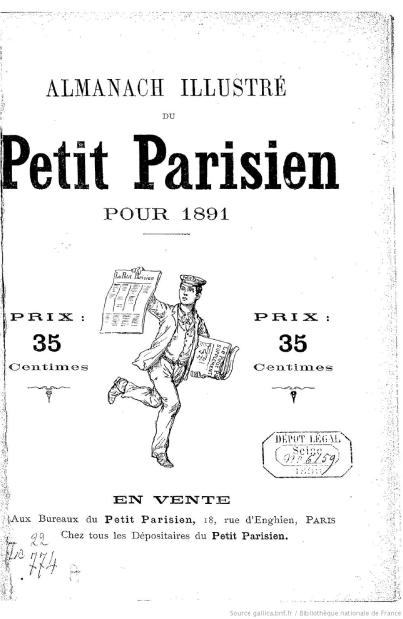

What possessed Jarry to create these two Almanacs? Well, almanacs were one of the earliest periodical publications in print history, but they were still being published and widely read around 1900 even though this period was in many ways the golden age of the newspaper. Popular newspapers like Le Petit Parisien issued almanacs every year. Some of these, such as the one below, you can find here on Gallica. They provided an overview of the year, practical information, a calendar, illustrations to the year’s main events. Like the weekly illustrated supplements the almanac was something readers might want to keep and preserve unlike the throwaway daily paper. They were also used as a promotional tool to lure subscribers to the paper.

What possessed Jarry to create these two Almanacs? Well, almanacs were one of the earliest periodical publications in print history, but they were still being published and widely read around 1900 even though this period was in many ways the golden age of the newspaper. Popular newspapers like Le Petit Parisien issued almanacs every year. Some of these, such as the one below, you can find here on Gallica. They provided an overview of the year, practical information, a calendar, illustrations to the year’s main events. Like the weekly illustrated supplements the almanac was something readers might want to keep and preserve unlike the throwaway daily paper. They were also used as a promotional tool to lure subscribers to the paper.

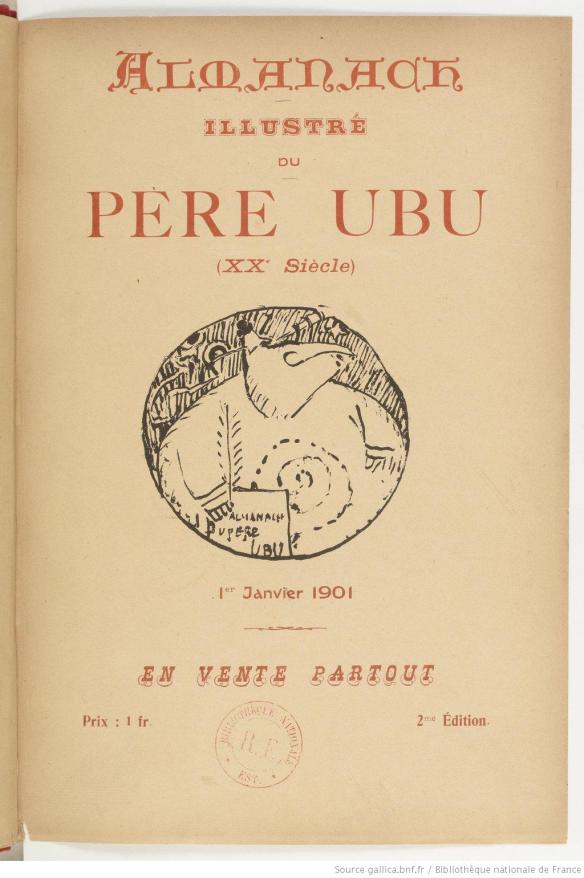

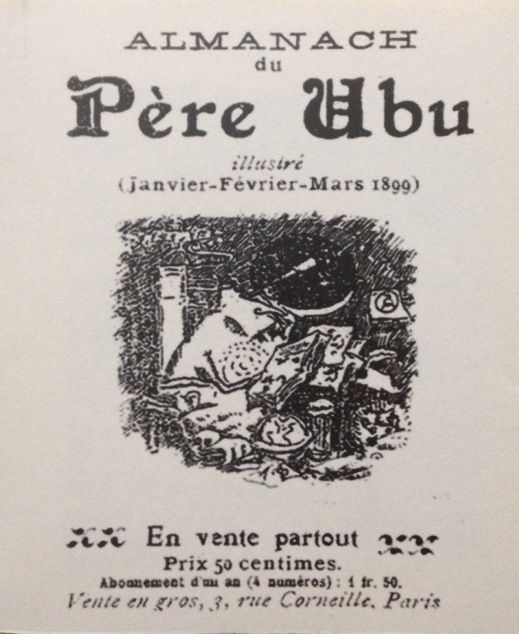

Promotion was no doubt one of the reasons Alfred Jarry came up with the idea of creating an Almanach du Père Ubu. After the tumultuous premiere of his play Ubu Roi in 1896 Jarry felt it was probably a good idea to capitalise on the notoriety he and his character Ubu had acquired. Despite the fact that the play had garnered lots of (negative) publicity and controversy, Jarry’s books still didn’t sell well. Jarry was still not a household name, but Ubu’s name was. The tourist guide Paris-Parisien (1899) even mentions Père Ubu among a list of important literary figure visitors to Paris should definitely be familiar with. So Jarry asked two of his friends, the visual artist Pierre Bonnard and composer Claude Terrasse to work with him on the first almanac. They must have thought that the name of Ubu alone would be able to carry such a publication as their own names are not mentioned as authors. They even saw opportunities for a periodical, because the original intention was to publish an Ubu almanac every three months. This never happened. The two publications, like all of Jarry’s work, never became a commercial success. Or a critical success for that matter. They were too absurd, too avant-garde, too marginal, too obscene. Or too bad? Who knows. Who cares. I like them.

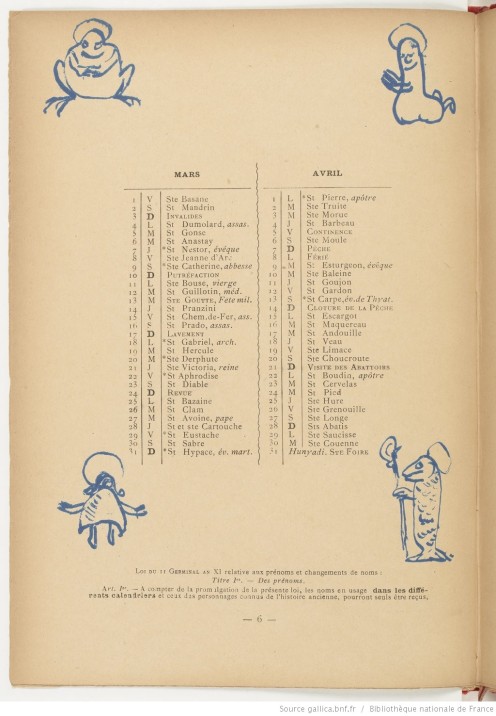

In true 1890’s avant-garde style both almanacs are a self-aware mix of literature, art, self-promotion, and a satirical take on news and newspapers. Both almanacs have their own calendar, full of real, obscene and imaginary saints as well as fake advertising or holidays invented by Ubu. Ubu treats us to his enlightened views on current issues such as the Dreyfus Affair, discusses events that haven’t happened yet, presents inventions that already exist, goes on imaginary journeys through the city of Paris, misbehaves himself in the colonies and awards well-known personalities with honorary titles in his own version of the Légion d’honneur. The almanac are absurd, irreverent, obscene, childish and created in the spirit of one Jarry’s heroes, Rabelais. Pierre Bonnard and Claude Terrasse not only contributed illustrations and musical scores, but also texts and ideas. It’s a shame I think that these works are not more widely known, but thanks to digitalisation they are at least available. The second one can be found online here on Gallica and the first almanac can be downloaded here as a pdf from the website of the Société des Amis d’Alfred Jarry. Even if you don’t read French, you can still enjoy the illustrations.

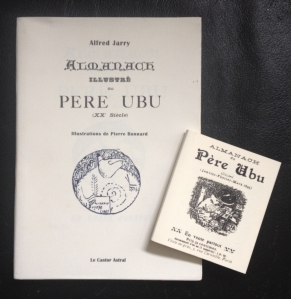

The first almanac was a tiny, pocket-size publication whereas the second one came in a more standard booklet format. The Société des amis d’Alfred Jarry has published a facsimile of the first almanac whereas the second almanac has also been republished by independent publisher Le Castor Astral. Here is a picture of the copies I own of those reproductions just to show how they differ in size. The first one really is small. It literally fits in one hand.

The first Almanac was written in a short period of time, probably at Claude Terrasse’s house in Montmartre in late 1898. We know for sure that the second one was written in a few days in December 1900 in the basement of the art gallery of Ambroise Vollard, the well-known art dealer. It was Vollard who also published the second one, a much more upscale edition as you can see from the picture above. The paper was of a higher quality, it had colour, larger illustrations and the price was higher too. Vollard was a clever businessman so he added the words ‘second edition’ en ‘for sale everywhere’ to the cover of the 1901 Almanac, even though this was clearly not the case. Vollard’s marketing trick failed. Just like the first one, the second almanac didn’t sell either. Most bookshops even refused to take any copies. But Ubu’s almanac did have admirers in artistic circles, such as Picasso and Apollinaire who both owned copies. Jarry’s work, his self-invented philosophy of ‘pataphysics, have inspired many artists, writers and thinkers to this day, evidenced by the various ‘pataphysical ‘clubs’ around the world. The original one, the Collège de Pataphysique, is also still going strong.

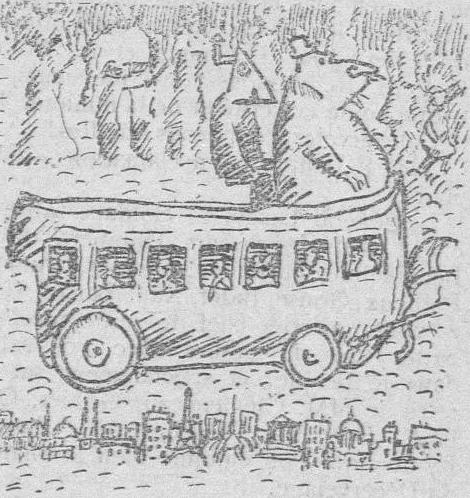

Much of the text of the Almanacs is not easy to comprehend today. A lot of the satire of current events is lost without any knowledge of said events or of how contemporary newspapers reported on them. Yet there is a lot of political satire in the two works even though Ubu’s language, full of puns, self-invented words and references to other artistic works, can be a challenge. The way Jarry ‘ubused‘ (as I called it in my book, probably thinking back then I was being very clever) the world around him and incorporated it in his work was nothing if not unique. There are still plenty of insider jokes, cultural and personal references to Jarry, his circle of friends that neither I or anyone else familiar with Jarry’s work have managed to figure out. But don’t be put off by that. Most of Pierre Bonnard’s illustrations are less ambiguous, whether it is Ubu riding in his ‘Omnubu’ through the city of Paris, Ubu standing in front of a kiosk or a praying penis with an aureola doodled in the margins of the calendar above. They speak for themselves. And both Almanacs can be enjoyed even without in-depth knowledge of the cultural-historical context. They certainly made me smile when I was revisiting them again this week.

Ubu and his companion, Monsieur Fourneau, drive the ‘Omnubu’ through the streets of Paris – Almanach du Père Ubu 1899, illustré

Both almanacs, apart from being a collaborative artistic project and promoting the Ubu works, satirise politics, the news and the way events were reported in newspapers. Among the avant-garde and cabaret culture of Montmartre in the late nineteenth century, parody and satire were en vogue. Mock news and satirical newspapers were a big part of this counter-culture and the humour of the Almanach du Père Ubu is very much indebted to that world. Jarry, Bonnard and Terrasse created their own alternative periodical as a creative, funny and highly necessary antidote to newspapers. This is how Père Ubu sells it anyway in his editorial to the first Almanac of 1899:

‘Princesses and princes, townsmen, villagers, soldiers, all ye faithful subscribers and buyers of our astrological Almanac, our beloved subjects, men and women, you won’t have to read any newspapers this winter. (…)So buy our Almanac. Our knowledge (…) renders tomorrow’s newspapers useless in advance.’

And there you have it. Fed up with newspapers? Then simply buy Père Ubu’s Almanac. Better yet, you can just download it for free these days using the sites I mentioned above. I wonder what Jarry would have thought about that? Well at least someone might read them now.

Further reading

If you want to know more about Jarry’s life I highly recommend the brilliant biography in English by Alastair Brotchie, Alfred Jarry: a pataphysical life (MIT Press, 2011). You can also find a nice taster on the wonderful Strange Flowers blog here. A good introduction to ‘pataphysics is Andrew Hugill’s book with the appropriate title Pataphysics: A Useless Guide (MIT Press, 2012).

If you want to learn more about the Almanacs, and yes, I am again embracing Jarry’s spirit of shameless self-promotion:

Dubbelboer, Marieke. The Subversive Poetics of Alfred Jarry. Ubusing Culture in the Almanachs du Père Ubu, Oxford, Legenda, 2012. http://www.legendabooks.com/titles/isbn/9781907747984.html

Béhar, Henri., Dubbelboer, Marieke & Morel, Jean-Paul (Eds.). Commentaires pour servir à la lecture de l’Almanach du Père Ubu illustré 1899, SAAJ & Du Lérot, 2009. ISBN: 9782355480225.

And for a great illustrated introduction to Montmartre’s counter-culture:

Cate, Philip Dennis & Mary Shaw, (Eds.). The Spirit of Montmartre. Cabarets, Humor, and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996.