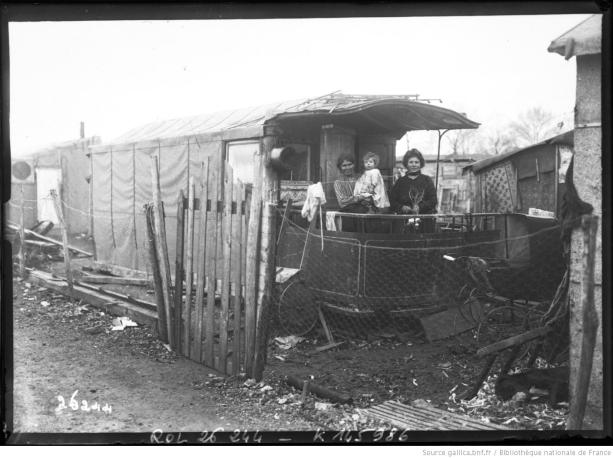

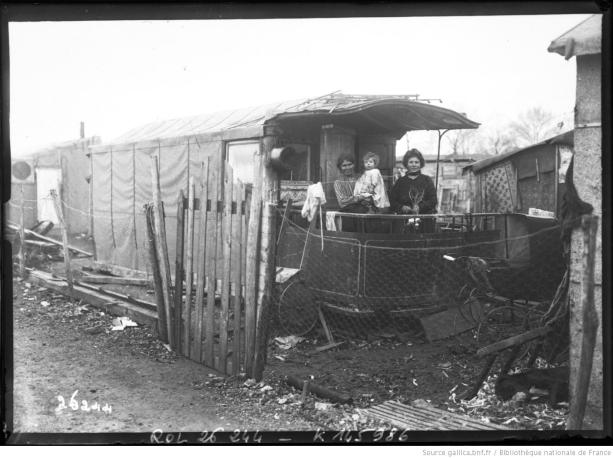

Zone inhabitants of Ivry in front of their ‘roulotte’, 1913, press photograph, Agence Rol.

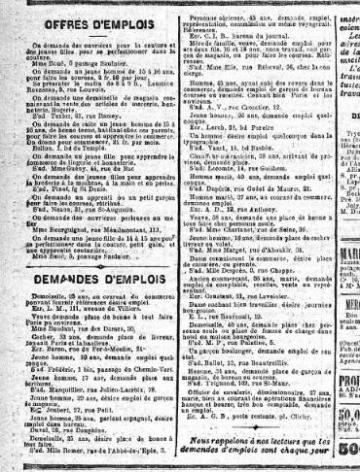

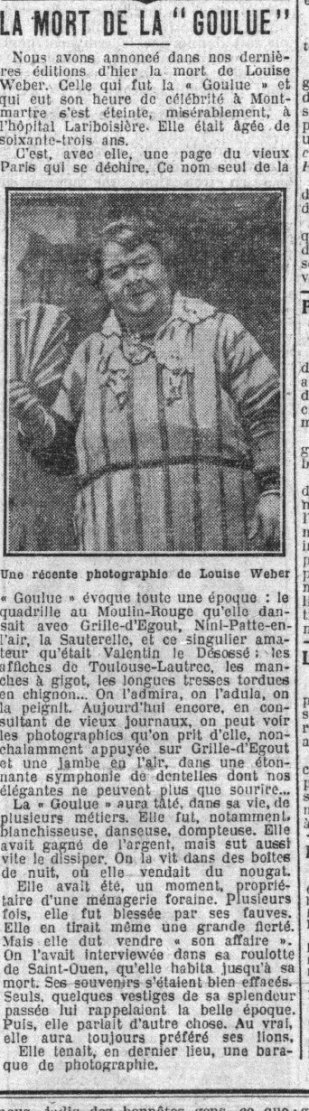

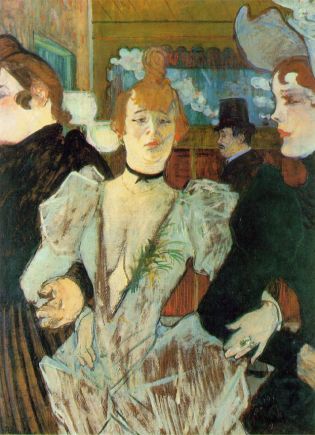

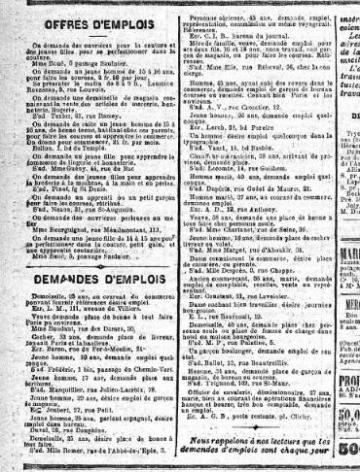

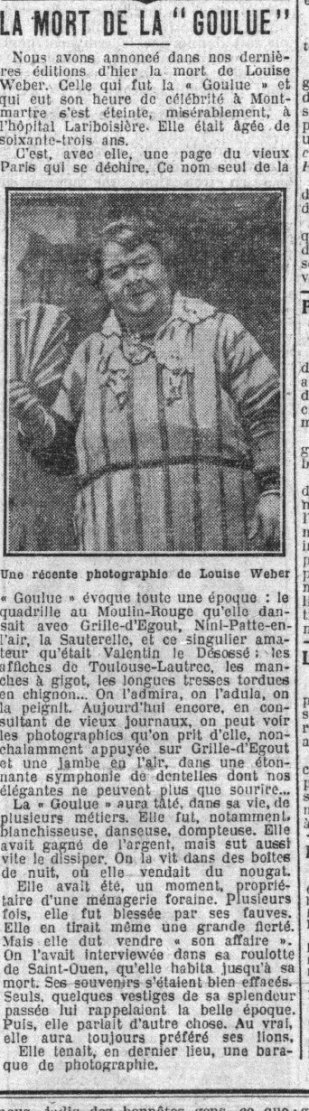

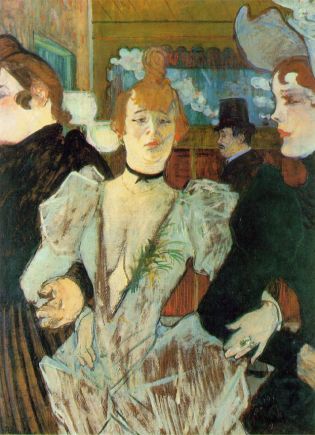

The exhibition Paris 1900, the City of entertainment has opened its doors to the public at Le Petit Palais. An iconic Toulouse-Lautrec image is used as the face of the exhibition. It plays on what many people already think of when they think of Paris 1900: carriages, elegant salons, theatres, cafes, the Moulin Rouge, sumptuous art deco design, the world exhibitions. According to the website the collection on display is ‘an invitation to the public to relive the splendour of the French capital.’ The exhibition aims to show the other side to this as well (prostitution, drugs), already present of course in Toulouse-Lautrec’s images. Yet the focus does appear to be very much on the glamorous and luxurious aspects, on this idea of a cultural bloom before the First World War altered everything. It made me think about the backgrounds of the people in Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters, about the less glamorous, everyday lives of Parisians at the time. And it made me remember the few glimpses of their lives I have come across in newspapers.  Such as here in L’Écho de Paris from 31 March 1886 where I was struck by the personal ads on page 4. Click here for the original on Gallica and a better resolution. Most of these are for jobs in service, not surprising considering the paper’s bourgeois audience. Demand for work greatly outnumbers the jobs on offer though and some of these ads are quite a depressing read: a 10 year old boy, a young single woman, an unemployed married man, all looking for a job. There’s a whole life behind these few words. What was their story? Did they get a job in the end? Life in service was not easy. Employers only had to give domestic servants 8 days notice if they wanted to get rid of them.[1] Salaries varied. Valets, coachmen and especially cooks could earn between 60 and 120 francs a month, but a ‘bonne à tout faire’, the general help, often earned little more than 1 franc a day.[2] The ‘fille de cuisine’, the kitchen maid, ‘should preferably never be seen.’ Still, it was better compared to many other options. Le Journal’s Saturday edition also had similar job and personal advertisements. Some are quite dubious. In the edition from 5 October 1895 an individual is advertising his range of ‘plusieures jeunes filles veuves et divorcées’ (several widowed and divorced young women). It is apparently up to the reader to guess what exactly these women were for. In other ads we encounter people who offer their money to make an investment or are seeking money from others to invest. Several are also from women who have fallen on hard times (or claim they have) such as in this one: jeune femme, du meill monde, honorable, tres gênée moment. Par suite de malheurs, dés. Empr. 300 fr. d’une pers. Sér. Et discr. Rembours ! Ecr. G.K.E. Jnal. young woman, from very good family, honourable, very short of money at the moment, due to misfortunes, seeks to borrow 300 fr. From Serious and discreet person. Will repay! Write G.K.E. Jnal. (Le Journal, Saturday 5 October 1895) I wondered how many reactions she would have received. Was it a scam? Who knows. Either way, what this ad and others show was the continuous quest for some sort of social and economic stability, whether through employment, marriage or slightly more questionable transactions. There was no safety net, no security. One event – a divorce, a family death, a bad investment, redundancy – could plunge anyone into instant poverty. The festive colours of many well-known Belle Époque images also stand in great contrast to contemporary press photographs or Eugen Atget’s album Zoniers (1913). See the original album here. Paris was expanding rapidly and couldn’t deal with the amount of people arriving in the capital looking for work. Photographers such as Atget and press agencies had begun to document the living conditions of people in the infamous zone, the slums all around the outskirts of the city. For an excellent visual, historical overview of the expansion of ‘la zone’ and Paris see Avant le périph’, la zone et les fortifs’ on the wonderful French blog Orion en aéroplane. Photography made these people visible to newspaper readers. Domestic servants were well off compared to the ‘zoniers’ who earned their money from recycling and selling small goods. One of the zone’s inhabitants was a woman who had once been a celebrated figure in the music-halls of 1890’s Paris. The singer Louise Weber, better known as La Goulue, was depicted at the height of her fame by Toulouse-Lautrec in several of his most famous posters. She went from being a celebrated Moulin Rouge star to spending the last years of her life in a caravan in one of the zones in Saint-Ouen, earning some money from selling snacks in nightclubs. Her obituary in Le Petit Parisien on 31 January 1929 movingly captures her trajectory from celebrity to poverty.

Such as here in L’Écho de Paris from 31 March 1886 where I was struck by the personal ads on page 4. Click here for the original on Gallica and a better resolution. Most of these are for jobs in service, not surprising considering the paper’s bourgeois audience. Demand for work greatly outnumbers the jobs on offer though and some of these ads are quite a depressing read: a 10 year old boy, a young single woman, an unemployed married man, all looking for a job. There’s a whole life behind these few words. What was their story? Did they get a job in the end? Life in service was not easy. Employers only had to give domestic servants 8 days notice if they wanted to get rid of them.[1] Salaries varied. Valets, coachmen and especially cooks could earn between 60 and 120 francs a month, but a ‘bonne à tout faire’, the general help, often earned little more than 1 franc a day.[2] The ‘fille de cuisine’, the kitchen maid, ‘should preferably never be seen.’ Still, it was better compared to many other options. Le Journal’s Saturday edition also had similar job and personal advertisements. Some are quite dubious. In the edition from 5 October 1895 an individual is advertising his range of ‘plusieures jeunes filles veuves et divorcées’ (several widowed and divorced young women). It is apparently up to the reader to guess what exactly these women were for. In other ads we encounter people who offer their money to make an investment or are seeking money from others to invest. Several are also from women who have fallen on hard times (or claim they have) such as in this one: jeune femme, du meill monde, honorable, tres gênée moment. Par suite de malheurs, dés. Empr. 300 fr. d’une pers. Sér. Et discr. Rembours ! Ecr. G.K.E. Jnal. young woman, from very good family, honourable, very short of money at the moment, due to misfortunes, seeks to borrow 300 fr. From Serious and discreet person. Will repay! Write G.K.E. Jnal. (Le Journal, Saturday 5 October 1895) I wondered how many reactions she would have received. Was it a scam? Who knows. Either way, what this ad and others show was the continuous quest for some sort of social and economic stability, whether through employment, marriage or slightly more questionable transactions. There was no safety net, no security. One event – a divorce, a family death, a bad investment, redundancy – could plunge anyone into instant poverty. The festive colours of many well-known Belle Époque images also stand in great contrast to contemporary press photographs or Eugen Atget’s album Zoniers (1913). See the original album here. Paris was expanding rapidly and couldn’t deal with the amount of people arriving in the capital looking for work. Photographers such as Atget and press agencies had begun to document the living conditions of people in the infamous zone, the slums all around the outskirts of the city. For an excellent visual, historical overview of the expansion of ‘la zone’ and Paris see Avant le périph’, la zone et les fortifs’ on the wonderful French blog Orion en aéroplane. Photography made these people visible to newspaper readers. Domestic servants were well off compared to the ‘zoniers’ who earned their money from recycling and selling small goods. One of the zone’s inhabitants was a woman who had once been a celebrated figure in the music-halls of 1890’s Paris. The singer Louise Weber, better known as La Goulue, was depicted at the height of her fame by Toulouse-Lautrec in several of his most famous posters. She went from being a celebrated Moulin Rouge star to spending the last years of her life in a caravan in one of the zones in Saint-Ouen, earning some money from selling snacks in nightclubs. Her obituary in Le Petit Parisien on 31 January 1929 movingly captures her trajectory from celebrity to poverty.

Le Petit Parisien, 31/1/1929, Gallica

Often the images we see of the period uphold this myth of a carefree, optimistic, fabulous period in the history of the city of Paris. And that was certainly part of the city’s life. Yet personal ads, photos of ‘la zone’, La Goulue’s personal story also show us the other side of the splendour; the socio-economic insecurity many experienced around 1900. This was also the Belle Époque. Not so ‘belle’ for most people.

Louise Weber in her glory years. Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, La Goulue arriving at the Moulin Rouge, 1892.

Update 5 May 2014:

Today I took a stroll around the Cimetiére Montmartre where La Goulue is buried. Go left on the roundabout close to the entrance and her grave is almost immediately on your left. It is maintained. And judging from the little bracelet and the fresh flowers left there, she still has admirers today.

Louise Weber’s grave at the Cimetiére Montmartre. Photo taken on 5 May 2014.

References:

[1] Paris-Parisien 1899, Paris, Ollendorff, p. 222.

[2] Ibid., p. 222

Fake Hindu dancer, traitor and ‘choreographic artist of foreign origin who lived in several European capitals’, Le Matin, 16 October 1917. Source: BnF/Gallica.

Fake Hindu dancer, traitor and ‘choreographic artist of foreign origin who lived in several European capitals’, Le Matin, 16 October 1917. Source: BnF/Gallica.

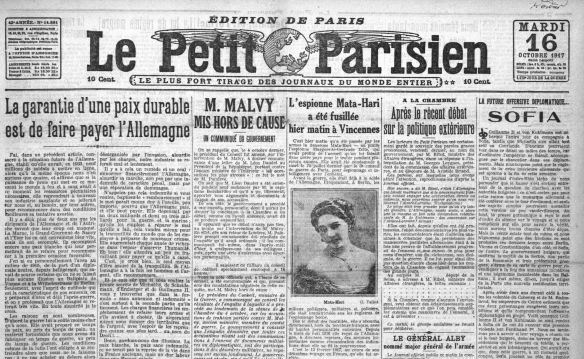

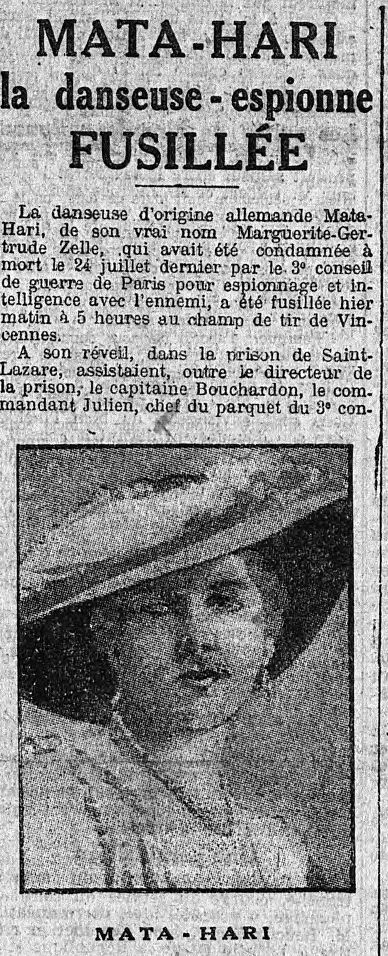

‘The dancer of German origin’ according to Le Petit Journal, 16 October 1917. The woman in the photo does not really look like her, but who cares, the spy is dead. Source: BnF/Gallica

‘The dancer of German origin’ according to Le Petit Journal, 16 October 1917. The woman in the photo does not really look like her, but who cares, the spy is dead. Source: BnF/Gallica