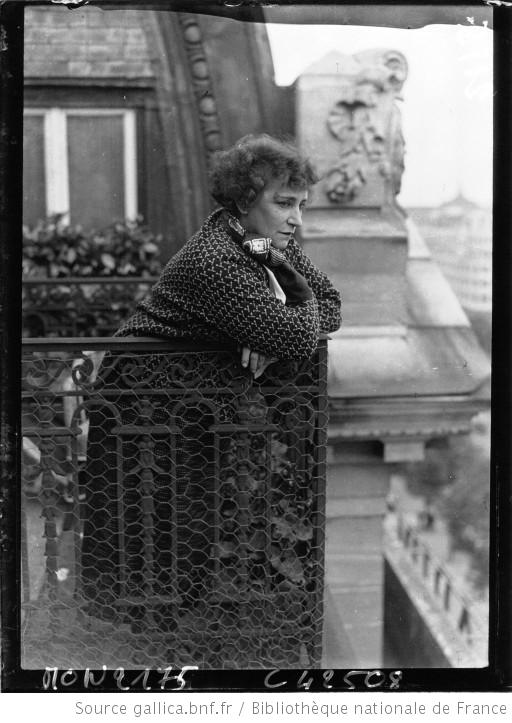

Colette in 1932, press photograph. Source: Gallica BnF

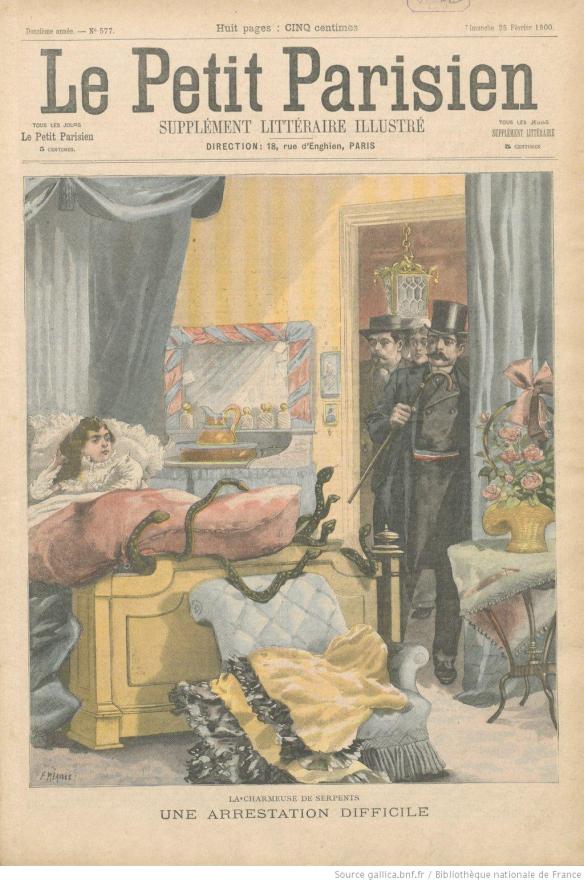

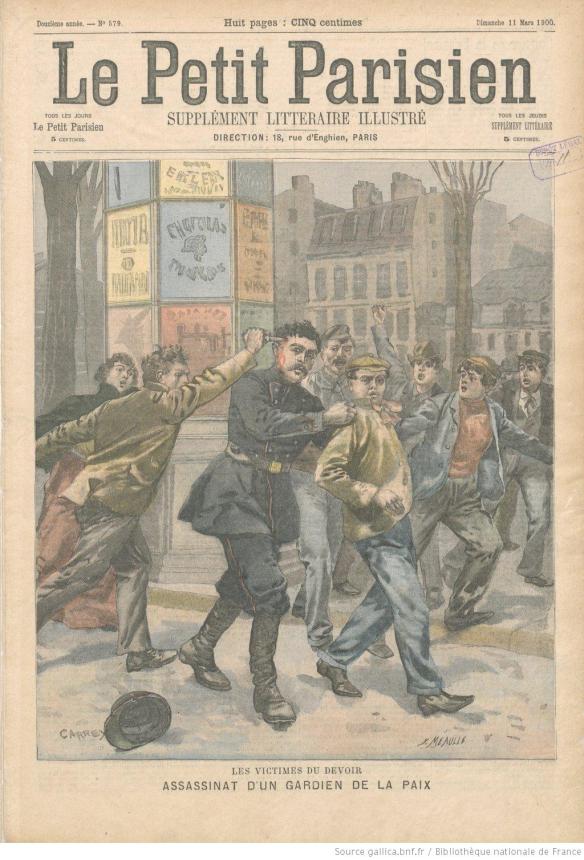

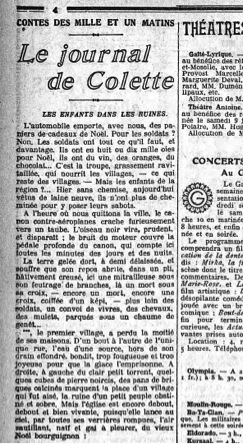

Shoddy journalistic stuff. That’s how Colette herself described the newspaper columns she wrote for Le Matin during the First World War. She was being a bit harsh. Perhaps because she preferred to be known for her literary work. Perhaps because she always had a tendency to downplay anything she wrote. But the fact was that she was a journalist. And she was good at it. Whether she liked it or not. I have been wanting to do a post on Colette and journalism for a while now. And since an academic article I wrote on her and the Belle Époque press was published last week this seemed like a good time for it. Somewhere in between her other writing, her theatre career and just living her life, Colette found the time to write an overwhelming amount of journalism. She tackled all sorts of subjects: war, crime, boxing, fashion, film, theatre, dieting. Her journalistic career spanned nearly half a century, starting in the early 1900’s and lasting almost up until her death in 1954. Her articles were published everywhere, cultural and literary periodicals, women’s magazines, fashion magazines, popular daily newspapers. Yet strangely enough very little has been said or written about her journalism. Shortly before the First World War Colette’s journalistic career received a real boost when she started to work for one of the biggest players in the French newspaper world, Le Matin. By 1913 Le Matin had become the second largest paper in France after Le Petit Parisien, selling almost a million copies a day. Colette was asked to write a weekly column entitled ‘Le journal de Colette.’ Colette’s name is hardly ever mentioned among the names of journalists who documented the war. Yet her articles on the First World War were deemed interesting enough at the time to be published. They appeared in a collection entitled Les Heures longues in 1917. The collection received good reviews, even though Colette herself called it ‘shoddy journalistic stuff.’ [1] During the war she travelled to Verdun, visiting her then husband who was in the army and witnessed the devastation first-hand. It wasn’t her style to write about the strategies or politics of war. Partly because it didn’t fit her writing, partly because it wasn’t very easy for any woman journalist to write about ‘hard news’ to begin with. But Colette wrote about the human cost of war, or the effects it had on those who stayed behind, women, children. Such as in the piece below from January 1915 titled ‘children among the ruins.’

‘Les enfants dans les ruines’ (Children among the ruins), Le Journal de Colette, Le Matin, 6 January 1915. Source: Gallica/BnF.

In 1914 Colette had said about her employment as a journalist for Le Matin: ‘il faut vivre’ (one has to make a living).[2] It’s true that she needed the regular income but Colette enjoyed the journalistic world, a world she would often reminisce about in her novels and stories. She loved how she had been one of the very first women to work as a court reporter for example. In 1933, when explaining her recent return to journalism, Colette gave a vivid description of her first impressions of the newspaper world in the 1890’s:

Where does this urge of mine come from. From way back when, when I was in my twenties. From my silent years, when I sat quietly observing Fouquier, Mendès, Courteline and Sarcey. From the former Écho de Paris, the Cocarde, the old Intransigeant…From the Rue du Croissant, the dirty editorial offices, where the gas made it impossible to breath. From the smell of ink, of men, of tobacco, damp mud and beer…[3]

If you would like to read more about Colette in the wider context of the Belle Époque press – and don’t mind academic writing too much- you can find my article in French Cultural Studies here. If you don’t have library access not to worry. A draft uncorrected version of that article can also be found on my Academia page. Follow the link in the About section above.

Better yet, if you want to read Colette’s original articles in Le Matin (provided you can read French), you can search for them here on Gallica. Luckily, digitalisation of newspapers and periodicals means that Colette’s journalistic writing is becoming more easily available. Let’s hope that will also spark a renewed interest in her journalistic work.

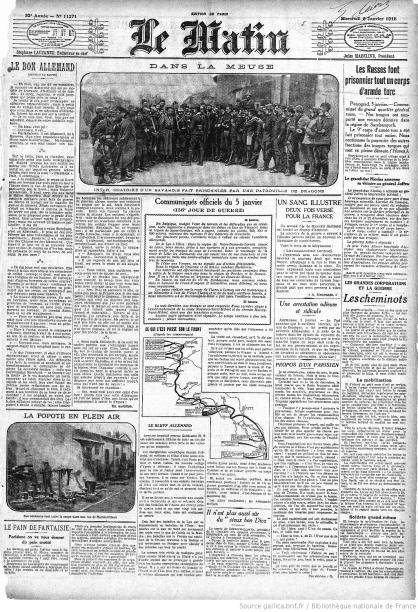

The front page of Le Matin on 6 January 1915. Colette’s column can be found on page 4, the last page. Most newspapers only had 4 pages at the time. Source: Gallica/BnF

NOTES

[1]‘pauvres choses journalistiques’ (letter to Francis Carco, July 1918) [2]Letter to Christiane Mendelys, 20 August 1914, cited in: Colette, Lettres de la vagabonde. Paris, Flammarion,1961, 107. [3] D’ou me vient cette tentation? De très loin, de ma vingtième année. D’un temps silencieux ou, silencieuse, je contemplai. De l’ancien Écho de Paris, de la Cocarde, du vieil Intransigeant…De la rue du Croissant, des salles de rédaction souillées, irrespirable, du gaz vert. De l’odeur d’encre, d’hommes, de gros tabac, de boue mouillée et de bière..Le Journal de Colette: On ne redevient pas journaliste’, La République, 15 December 1933. Cited in: Gerard Bonal and Frederic Maget (ed.), Colette journaliste. Chroniques et reportages 1893-1955, Seuil, 2010, 35. This book is, apart from articles in the Cahiers Colette, the only recent publication to focus on her journalism. Translation done in haste by me.